Party School Pride

Picking a college can be an arduous process. In selecting a school, students weigh several essential factors such as price, prestige, and proximity to home. For some students, the final decision may include an entirely different aspect of the college experience – a priority they’re unlikely to share with their parents. Being away from home for extended periods of time, having more independence, and forming new friend groups give students more reasons to let loose and party. Even though they are there for all the academic benefits of higher education, some students are far more interested in opportunities to party.And if recent research is any indication, students in search of intoxicated fun rarely struggle to find it.

How much do prospective students value a college’s party scene? How do drinking behaviors shift once students arrive on campus? And do graduates eventually regret their partying experiences, later wishing they’d showed more restraint?

We surveyed 1,083 college graduates, asking them how much the promise of partying influenced their college choice and how they used drugs and alcohol in their undergraduate years. Our findings reveal the expectations and realities of college partying and how certain attitudes and experiences shape substance use. Our graduates reflected on their partying with an interesting mix of pride, remorse, nostalgia, and nausea. To see how their college experiences compare to your own, keep reading.

Matriculation Motives

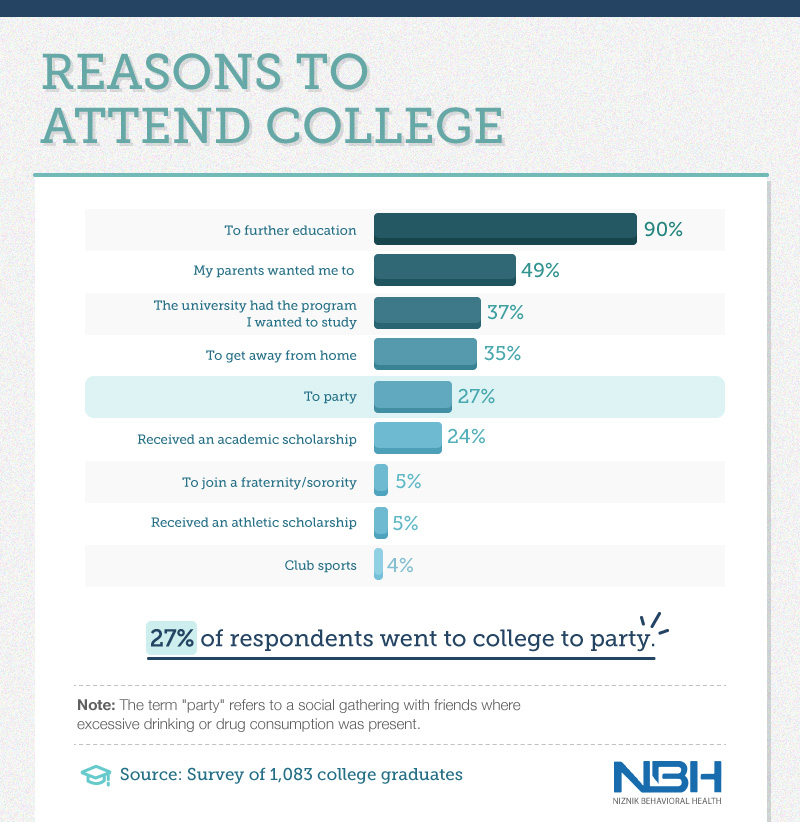

As far as the impetus of college attendance, educational concerns remain essential: 9 in 10 respondents said they went to school to further their studies. Indeed, with more Americans attending college than ever before, many view an undergraduate degree as a minimum requirement for professional success. Nearly half of respondents, however, said their decision to attend college reflected their parents’ wishes. Perhaps in reaction to parental pressure, another 35 percent said they went to college to get away from home.

While the desire to party ranked behind these concerns, 27 percent said the allure of college ragers influenced their decision to enroll.Their impressions may be influenced by media portrayals of college debauchery or widely scrutinized party school rankings, which pit alcohol-intensive campuses against one another annually. In fact, partying was more often a factor in the college decision than academic scholarships. Furthermore, merely 5 percent said their decision related to an athletic scholarship (just 2 percent of all high school athletes receive a sports scholarship).

Partying Proclivities, by College Type and Major

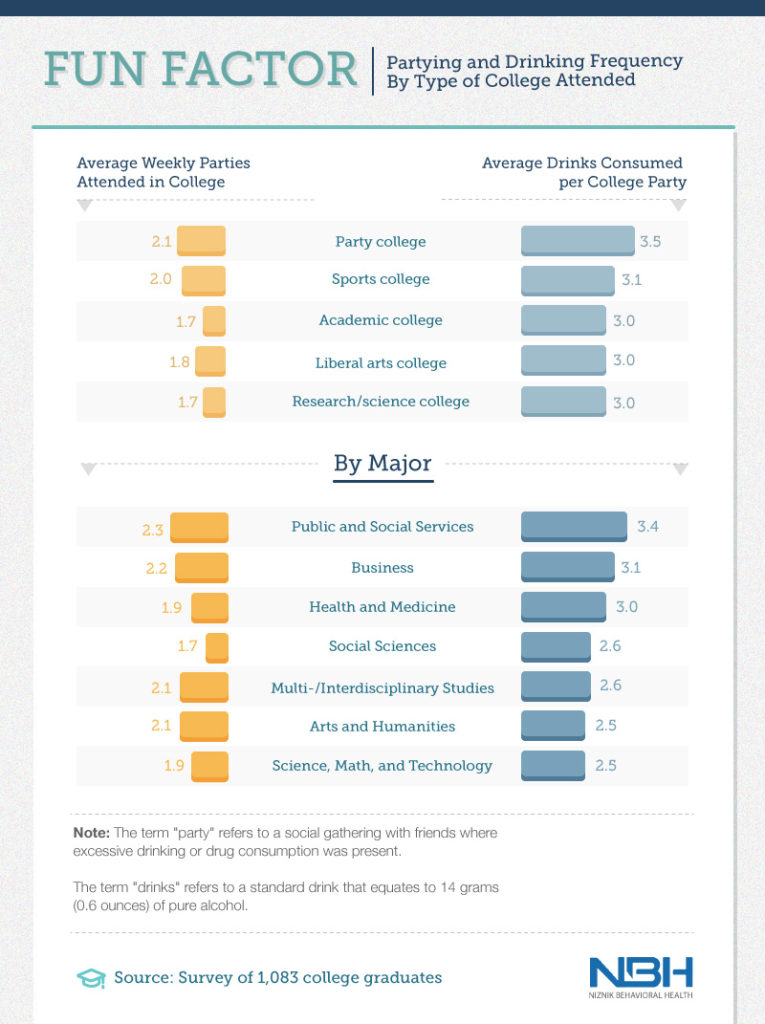

The landscape of higher education includes a diverse array of institutions, from small colleges to major research universities. Our findings indicate that party attendance varied relatively little across the spectrum of college types, although respondents who went to a “party school” did attend the most parties on average. This group also consumed the most drinks on average, putting down 3.5 drinks per party. Those who went to sports colleges, where boozy tailgating traditions are integral to campus culture, ranked second overall in party attendance and drinks consumed on average.

Request a Call to Speak to a Coordinator Today.

We found interesting variations among majors as well. Arts and Humanities, Science, Math, and Technology students attended the fewest parties on average, followed by those in majors related to Social sciences and Multi-/Interdisciplinary. These findings could reflect the rigors of these academic disciplines: Pre-med students, for example, may struggle to balance their coursework with partying. Conversely, students studying public and social services (such as law, social work, or criminal justice) attended the most parties and consumed the most drinks on average. These findings resonate with evidence of substance abuse in related fields: Alcoholism is particularly prevalent among legal and law enforcement professionals.

Counterfeit Cards

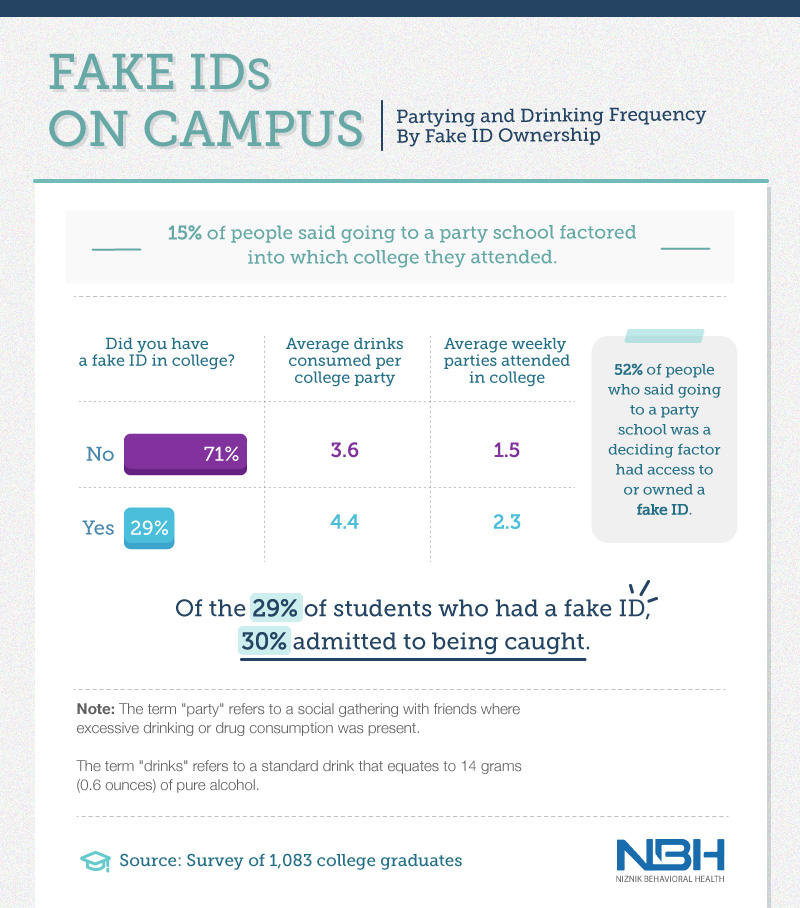

Although colleges have seen an influx of older students in recent years, many underclassmen are still too young to consume alcohol legally. Among our respondents, roughly 3 in 10 possessed a fake ID at some point in college. On average, this group attended more parties than the contingent without fake IDs and consumed more drinks on each of these occasions.

This data could simply reflect access: When one has the means to purchase alcohol, a higher rate of consumption becomes possible.But the connection between fake IDs and increased partying might also reflect students’ intentions. Among respondents who said attending a party school was a decisive factor in their college choice, more than half had fake IDs.

But if fake IDs were common among students who planned to party, they frequently led to trouble as well. Thirty percent of respondents who had fake IDs admitted to getting caught with their counterfeit credentials. And while getting caught often results in nothing more than a stern warning, some students can also face serious legal ramifications. While penalties vary by state, individuals with fake IDs can potentially be charged with a misdemeanor or a felony.

Intoxication Intensification?

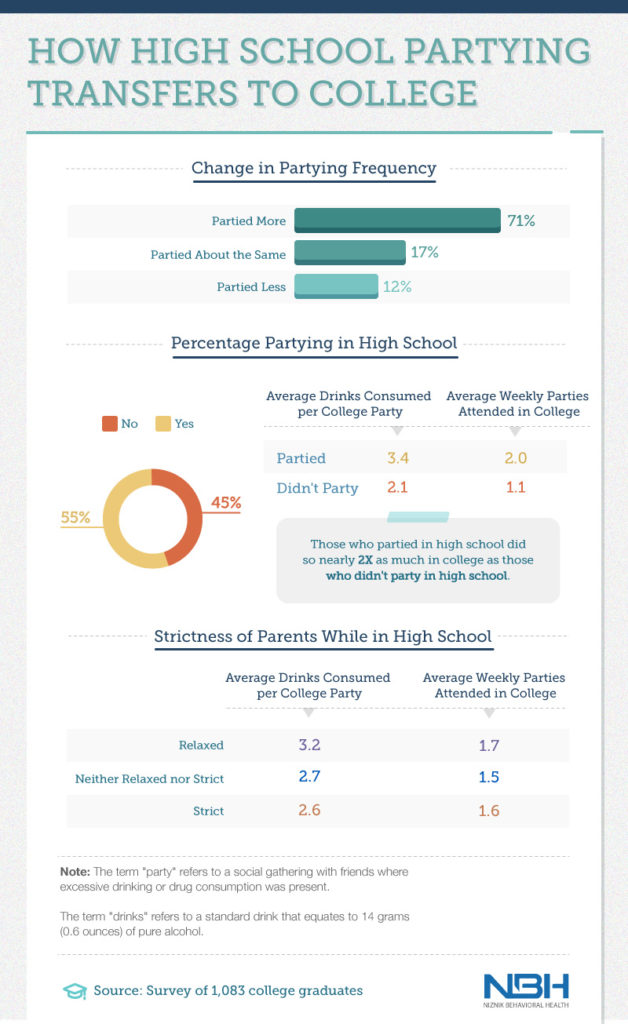

Seventy-one percent of respondents recalled that their partying increased upon reaching college, and merely 13 percent said they actually partied less than they had in high school. That shift could reflect minor experimentation: Since 45 percent said they hadn’t partied before college, any drinking at all would represent an increase.

Yet, those who had partied in high school drank substantially more in college, consuming 3.4 drinks at each party on average. Research does suggest that individuals who start drinking early often use alcohol more intensely later in life. Among experts, drinking in the early teen years is considered a significant risk factor for the subsequent development of substance use disorders.

Accordingly, many parents attempt to dissuade their teens from experimenting with alcohol in high school, imposing strict rules or harsh penalties. Our findings suggest such tactics may also inhibit drinking once students reach college. Respondents whose parents were “strict” about partying consumed 2.6 drinks, on average, at each party, compared to 3.2 drinks for students whose parents adopted a “relaxed” approach. Yet, respondents whose parents took a more moderate stance consumed 2.7 drinks per party, suggesting a balanced approach may be just as effective.

The Price of Partying

Our findings indicate that partying habits tend to increase slightly as students advance through college. Whereas freshman attended just 1.6 parties a week on average, juniors and seniors typically went to two. Likewise, seniors consumed approximately half a drink more at each party than freshmen. This trajectory translates to added expenses, with weekly alcohol spending increasing 57 percent across the typical student’s college career. These costs could reflect more than personal consumption: Students old enough to buy alcohol may purchase booze for others as well.

On average, men spent approximately $4 more each week on drinks than women – perhaps because men often require more alcohol than women to obtain the same effects. Those in fraternities and sororities also spent more, on average, than their non-Greek peers. Among different majors, those studying business were the biggest spenders, followed by students pursuing degrees in public and social services. Regardless of what one studies, however, many students can ill afford to spend hundreds of dollars on alcohol each semester. According to one recent study, more than a third of college students struggle to afford food, let alone nights out drinking.

Going Greek, Getting Wasted

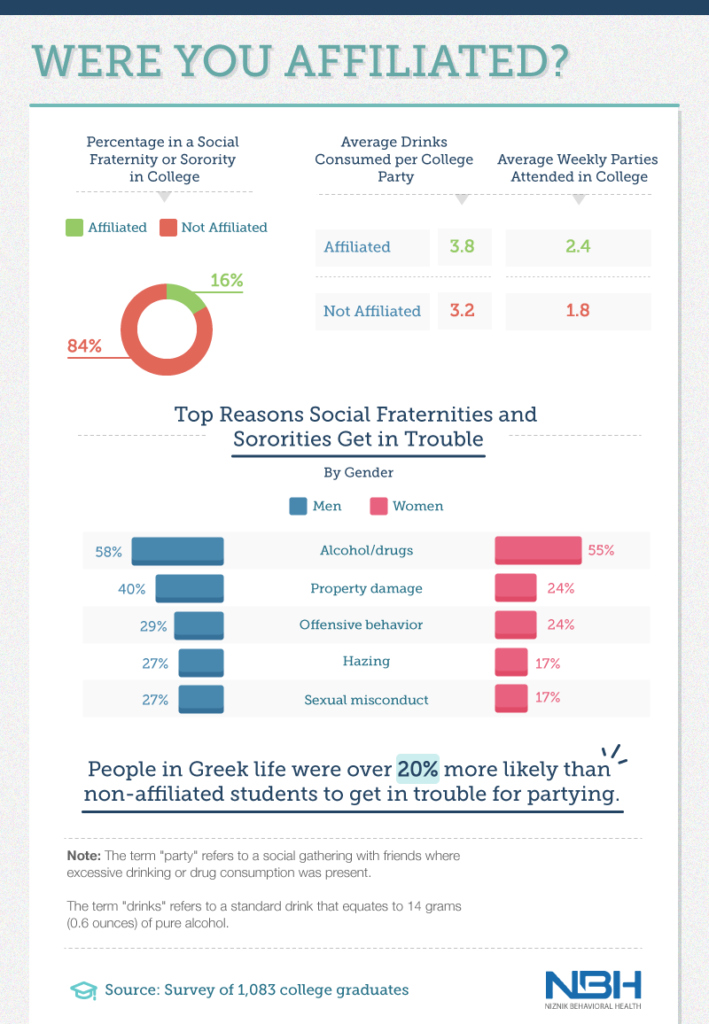

Despite a recent string of tragedies involving Greek life and alcohol, fraternities and sororities remain immensely popular with American college students. Sixteen percent of respondents reported participating in Greek life while in college, and these cohorts tended to party more intensely than those with no fraternity or sorority ties.

Request a Call to Speak to a Coordinator Today.

Students partaking in Greek life were most likely to get in trouble for using drugs and alcohol, but they were also disciplined quite often for actions that likely involved intoxication. Fraternity brothers were particularly likely to cause property damage, for example. More serious incidents, including hazing and sexual misconduct, were also quite common (these issues represent major concerns for administrators across the country).

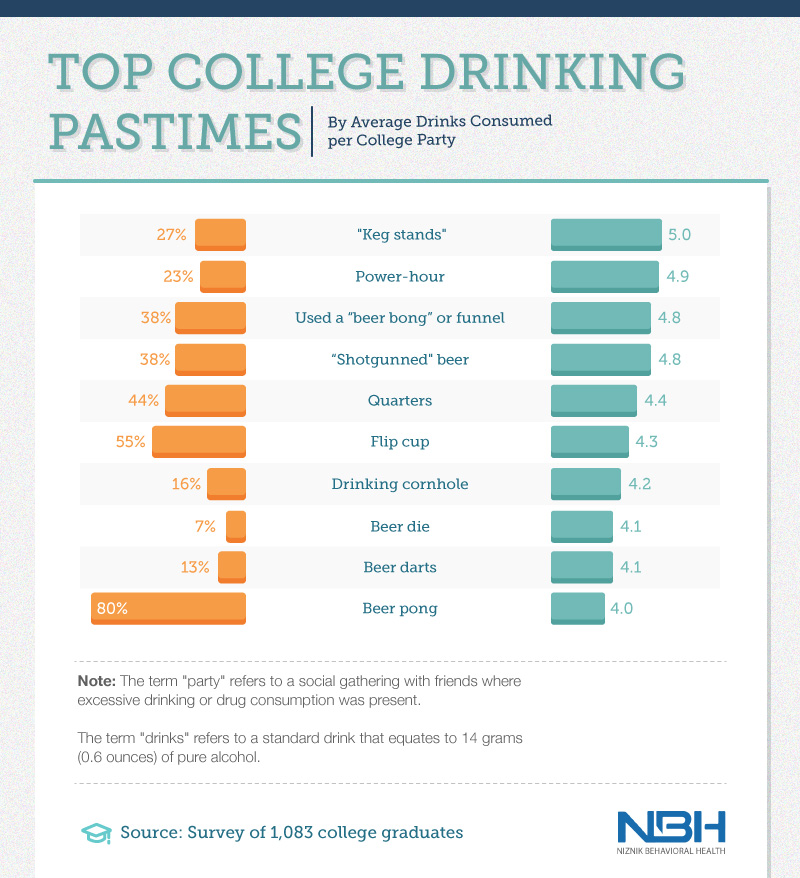

When one considers the most common college drinking games, it’s not hard to imagine how partying could quickly turn dangerous or destructive. Beer pong, Flip Cup, and quarters involve downing multiple drinks in rapid succession, sometimes for several rounds in one sitting.

Getting Caught – and Other Consequences

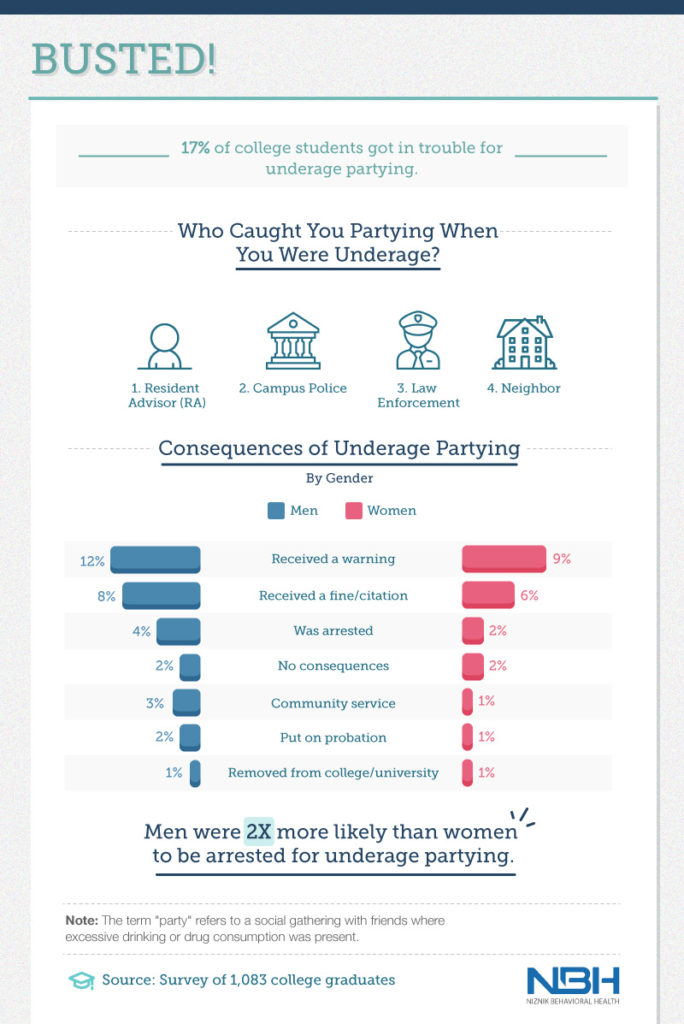

Seventeen percent of respondents reported getting in trouble for underage partying at some point during their college careers.But their experiences differed significantly according to the particular authorities who caught them in the act. Students were most likely to be caught by resident advisors, followed by campus police. In recent years, the actions of campus police officers have prompted outrage at some colleges, causing experts to question their use of force against students who are under the influence or experiencing mental health issues. Additionally, students were often caught by law enforcement and their neighbors.

The most common outcome of these incidents was a warning, but students frequently suffered more serious consequences as well. Men were particularly likely to report serious punishments, with 8 percent receiving a fine or citation, and 4 percent getting arrested. Such arrests may result from alcohol-fueled violence: According to experts, nearly 700,000 college students a year are physically assaulted by another student who is under the influence of alcohol. These actions could also result in expulsion. One percent of respondents said they’d been removed from their school as a result of underage partying.

Yet, many grave consequences stemming from college drinking are not imposed by outside authorities. Several of our respondents reported that their grades suffered when hangovers prevented them from performing well on exams. Moreover, some respondents risked injury while intoxicated, such as one young man who fell down a flight of stairs. These incidents recall the death of Timothy Piazza, a young man who fell down a flight of stairs during an alcohol-fueled fraternity initiation event. Hours later, he died of his injuries.

Regrets and the Real World

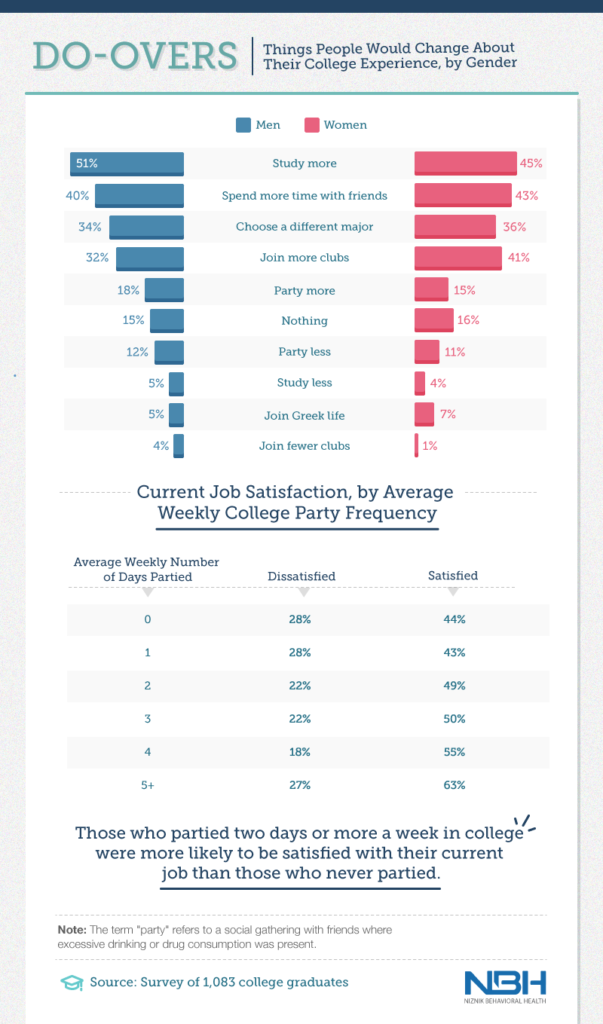

Reflecting on their undergraduate years, our respondents frequently expressed the wish that they’d used their time differently. Academic remorse was quite common: 51 percent of men and 45 percent of women wished they’d studied more often, and more than third of men and women would have selected a different major. Many others regretted not joining more clubs available on campus. Conversely, just 18 percent of men and 15 percent of women wished they had partied more during their college experience. But even fewer respondents wished they’d partied less, suggesting most people see their exploits in college as acceptable in retrospect.

In a counterintuitive twist, intense partying in college seemed to correlate with increased job satisfaction. Among those who had partied four days a week in college, 55 percent were satisfied with their professional circumstances. By contrast, among those who partied one day or less each week in college, fewer than 45 percent were satisfied with their jobs. These findings may relate to a disturbing trend among high-achievers: Those who are particularly driven in their early lives frequently feel dissatisfied in later years, despite their considerable success.

College Consequences, Adult Implications

Our findings suggest that few students consider partying alone when selecting their colleges. But that finding may simply reflect the prevalence of alcohol and drugs across campuses: At small schools and large universities alike, undergraduates attend parties quite regularly. Accordingly, most college students drink more than they did previously and frequently encounter negative outcomes. From monetary costs to severe legal consequences, the risks of intoxication are evident in our data.

Yet, the most common college partying regrets concerned missed opportunities. In retrospect, a large percentage of graduates wished they’d been more devoted to their studies and their friends. In other words, drinking can sometimes obscure the reasons that people choose their schools in the first place.

Substance use should never jeopardize an individual’s personal priorities, in college or at any other stage of life. If someone you love is suffering as a result of his or her drinking or drug use, real change is possible with the right help. Talk to our team to learn how Niznik Behavioral Health provides substance use treatment of the highest quality.

Methodology

There were 1,886 respondents from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. However, 803 respondents did not meet the qualifications to participate in this study, leaving 1,083 able participants. The respondents who were excluded stated they did not attend or complete college. Throughout the survey, outliers were excluded from our data. From the able respondents, 49 percent were women, and 51 percent were men. Our respondents ranged in age from 18 to 77 with a mean of 33 and a standard deviation of 10.68.

Limitations

The data throughout this campaign relies on self-reporting. As a result, there is known to be many issues with self-reported data. These issues include but are not limited to: selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and exaggeration.

Sources

- https://www.cdc.gov/features/teen-substance-use/index.html

- https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/time-for-parents-discuss-risks-college-drinking

Fair Use Statement

Want to share the good, bad, and ugly of college partying? Feel free to use our content on social media or your own site for noncommercial purposes. We do request that you link back to this page whenever you use our work to attribute our team. As with any college paper, you should always cite your sources.